The Perfect Wooden Cutting Board

12th Nov 2019

Wood makes the best cutting boards, nearly everyone agrees. Here are 10 traits you need to evaluate in cutting boards and butcher blocks, along with examples of boards that excel.

Aesthetic appeal

Board beauty is subjective and can depend on everything from the decor in your kitchen to your preference for light or dark wood. Still, this factor shouldn't be neglected, since part of the joy of having a wooden cutting board (especially compared with a plastic board) is the good looks—and the good feel. Don't forget about the feel and sound of the knife when it strikes the board (more on that later).

One way to think about it is if you like certain woods in furniture, why not choose the same for your counter-top furniture? Some woods,

such as oak, look relatively plain when cut one way but reveal classic beauty when quarter-sawn, or sliced along a line that passes through the center of the log. Treeboard's edge-grain boards all use quarter-sawn oak.

such as oak, look relatively plain when cut one way but reveal classic beauty when quarter-sawn, or sliced along a line that passes through the center of the log. Treeboard's edge-grain boards all use quarter-sawn oak.

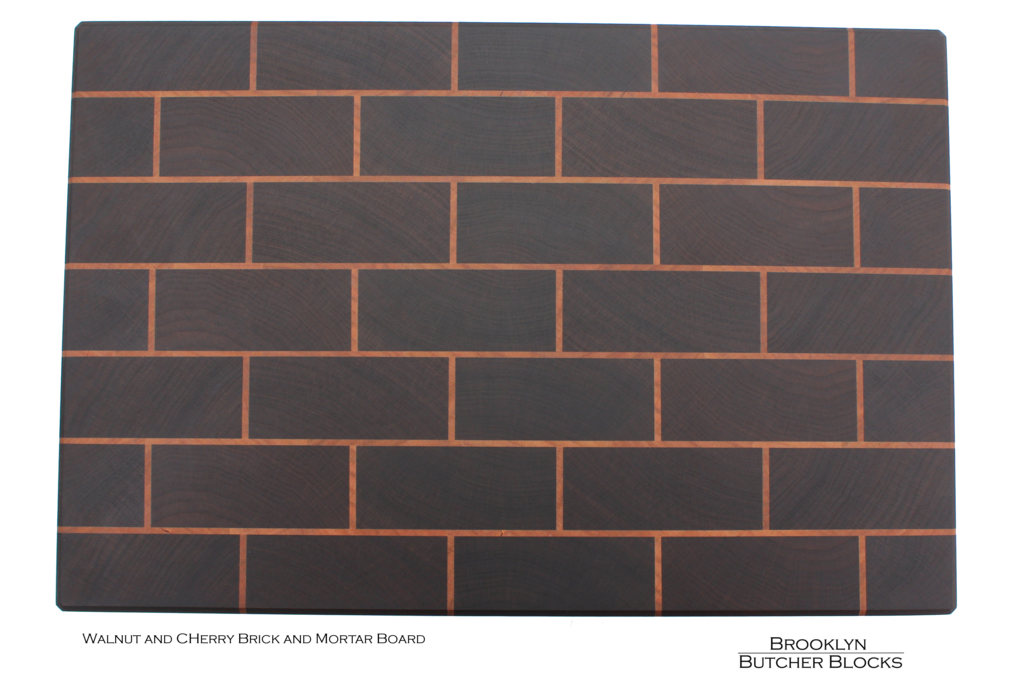

Many cooks don't mind a glued-up board with strips of wood, but others prefer a solid piece of timber for its wild, natural look. A laminated or composite board should have some special visual appeal to compete with natural timber. One knockout example is the end-grain walnut-and-cherry board from Brooklyn Butcher Blocks, which resembles the brownstone masonry of New York City. One note: Dark woods may hide stains better, but if you oil boards and wipe after each use, stains shouldn't be a problem.

Species

Some of the traditional hardwoods used in furniture—maple, oak, cherry, walnut and oak—are also great for cutting boards and butcher blocks. So are beech and teak. You just have to watch out for aromatic woods that can impart an unwanted smell or flavor to food, as well as some exotic species that can have toxic oils. A good rule of thumb is using trees that produce edible fruit and

nuts. Bob Vila's home advice website ranks maple as the best wood for cutting boards. Others like teak because its natural oils make it relatively low maintenance. One caution about tropical woods: the trees can be cut indiscriminately, and sometimes logging supports unsavory regimes in Burma or other countries. One final note on species: bamboo isn't a tree at all—it's grass.

nuts. Bob Vila's home advice website ranks maple as the best wood for cutting boards. Others like teak because its natural oils make it relatively low maintenance. One caution about tropical woods: the trees can be cut indiscriminately, and sometimes logging supports unsavory regimes in Burma or other countries. One final note on species: bamboo isn't a tree at all—it's grass.

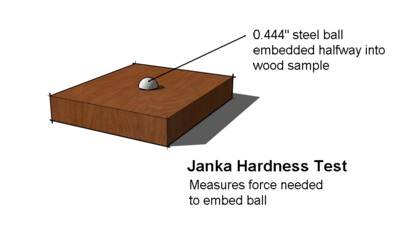

Hardness

You can measure rocks by how easy it is to scratch them, but wood's hardness is calculated by the amount of force it takes to press a steel ball into a board, known as the Janka hardness. In general, harder is better, since  boards should be durable. White oak has a hardness of 1,350 pounds, meaning it takes that amount of force to push a ball that's 4/9 of an inch in diameter halfway into the board. Maple can range from 700 to as hard as 1,450, depending on the species, with teak coming in at 1,070. Pine, while pleasantly aromatic, is generally unsuitable for serious cutting boards (eastern white pine has a Janka hardness of just 380 pounds). Balsa wood comes in at 67 pounds, since the wood is literally sold for hobbyists to cut it up with knives.

boards should be durable. White oak has a hardness of 1,350 pounds, meaning it takes that amount of force to push a ball that's 4/9 of an inch in diameter halfway into the board. Maple can range from 700 to as hard as 1,450, depending on the species, with teak coming in at 1,070. Pine, while pleasantly aromatic, is generally unsuitable for serious cutting boards (eastern white pine has a Janka hardness of just 380 pounds). Balsa wood comes in at 67 pounds, since the wood is literally sold for hobbyists to cut it up with knives.

Grain alignment

Now we're getting to some of the delicate issues that separate the real butcher's delight from the discount-store special. Many top-of-the-line cutting boards and butcher blocks feature end grain, which means the grain of the wood is essentially running vertically from the counter top straight up to the food and your knife. The advantage of end grain is that it allows the knife to split into the outer top of the wood, sparing it a jarring encounter with the edge of the grain. Those little splits can be "healed" with the addition of oil or wax (see below) or sanded off. On the other hand, edge-grain boards, seen frequently in boards made of rectangular strips, are typically more durable for chefs and butchers who are going to be sharpening their knives anyway. So it comes down to whether you want to spend time renewing your board or your knife edge or both. One compromise, featured in Treeboard's collection, might be using edge-grain bards with the grain going toward you, rather than alongside the width of the counter. In that case the knife would be cutting along the grain rather than across it. (Thoughts on this welcome in the comment section below.)

Knife friendliness

From the point of view of your kitchen ginsu, the issues of grain alignment and hardness discussed above are most of what you need to know. One further issue is that fast-growing or tropical woods high in silica can hurt knives. Also bamboo. Overall, wooden cutting boards are much easier on knives than plastic, and stone is downright scary for your cleaver.

Warp resistance

Any pieces of wood will crack or distort, given the wrong combination of wetting and drying cycles. Furniture is protected from this by a hard finish, but cutting boards frequently have their finish sliced so don't have this luxury. The main way cutting-board manufacturers minimize overall warping is by alternating strips of wood with the grain angled in opposite directions. In that case, a tendency for one strip to warp in one direction is counteracted by the next strip warping the other way.

End-grain boards, such as appear to sidestep the warping problem, since they expand mostly up and down after absorbing moisture. The John Boos end-grain boards—made of a checkerboard of square sections—are some of the best known on the market.

Another solution is cutting a prime slice of wood to deter warping. For centuries, furniture makers and musical-instrument artisans have relied on quarter-sawn wood to produce stable tables, chairs and drawers, especially before the advent of climate-controlled buildings. The same idea seems to work for the humble cutting board, since boards cut radially through the center of logs have a better balance when moisture creeps in. You can recognize quarter-sawn boards, including Treeboard's new collection, by the vertical grain pattern on either end or the ray flecks on the board's face.

Heft

Unlike a wooden surfboard, a wooden cutting board is meant to be heavy. The more weight an object has the more friction, and you don't want your block to slip and slide when cutting sushi or turkey. An added benefit is that thicker boards can be cut nearly to pieces, then easily renewed with by sanding or planing and the application of more oil. Plastic boards and thin wooden boards can be sold cheaply since they use less material and ship with more boards to a box. But unless we're talking about a coaster-sized square for serving cheese, you're better off with the big boards.

Custom touches

Some people want finger grooves on the side to use as handles. Others want a juice canal to catch roast-beef juices or tomato pulp. Still others want rubber feet. One producer even dared to put a rack for cell phones so that you can read the recipe while chopping liver and onions. Not sure you want electronics anywhere near me when I'm swinging a knife, but the point is that the cutting boards need not be primitive and can be customized to your needs.

Pores

Pick up a magnifying glass and look at a piece of wood and you'll see the beautiful details of the grain and even individual cells. The problem is that large or deep pores can harbor bacteria if not filled with a suitable finish. Overall its better to choose fine-grained woods such as maple, cherry or beech. The exact species sometimes matters, as red oak is so full of holes that you can blow bubbles with it, while white oak has special cells that block the pores, making for a more sanitary kitchen product.

Natural finish

Cutting boards are different from violins and table tops, which often sport a crisp varnish on the outside. Yet that varnish quickly turns into polymer shreds under the influence of your favorite kitchen knife. So instead you need a softer, natural, easily renewable finish that relies on natural oils and waxes. Some companies sell mineral oil blends, which come from petroleum. One popular product is Odie's Oil, a food-safe proprietary blend of lubricating oil, drying oil, natural waxes and essential oil, according to the product's safety data sheet.

Many woodworkers like to keep it simple, with natural oils that dry over time into polymers. The best-known examples are tung oil and linseed oil. Linseed oil should be "raw" and not "boiled," since boiled linseed oil actually includes chemical catalysts designed to help the oil dry more quickly.